Introduction

The twenty-first century has witnessed a profound reconfiguration of global power, driven by the digital revolution. The rivalry between the United States and China extends far beyond traditional statecraft, encompassing cyberspace, telecommunications, artificial intelligence, and control over digital infrastructure (World Bank, 2024; Jin, 2025; OECD, 2023). These two powers are no longer simply economic and military competitors; they are locked in a battle to define the technological future of the world. This contest is not merely bilateral but fundamentally systemic, shaping the architecture of the international order for decades to come.

As of 2025, this competition has intensified across three critical dimensions: technological supremacy, digital sovereignty, and diplomatic influence in the global digital space. The contest is not solely about national prosperity or security, but about whose values, governance models, and standards will underpin the digital era. Both countries use their technological prowess as tools of influence, leveraging state-led industrial policy, strategic alliances, and regulatory frameworks to expand their global reach. The resulting fragmentation of the digital order threatens to create parallel digital spheres, with profound implications not only for great powers but for the entirety of the international community.

Hypothesis and Objectives

This paper hypothesizes that US–China competition over digital infrastructure, technological standards, and data sovereignty is fragmenting the global digital order, undermining cooperative governance and fueling new forms of dependency among third countries. This fragmentation risks institutionalizing a “digital iron curtain,” where incompatible technical standards, regulatory approaches, and security doctrines impede global flows of data, talent, and innovation.

Specifically, this analysis addresses:

- How has the US–China digital rivalry altered global governance and security paradigms, and to what extent does it challenge the multilateral system?

- What are the drivers and impacts of their competing models for digital infrastructure and data governance, and how do they shape global value chains?

- How are third countries, particularly in Latin America, responding to and shaped by this bifurcation, and what agency do they retain amid rising dependency?

Justification and Figures

The stakes could not be higher. The digital economy’s exponential growth—$15.5 trillion in 2023 (16 % of world GDP), projected to exceed 25 % by 2030—makes technological leadership the defining source of national power and prosperity (World Bank, 2024). China and the US together account for over 60 % of this digital economy, amplifying the global impact of their rivalry.

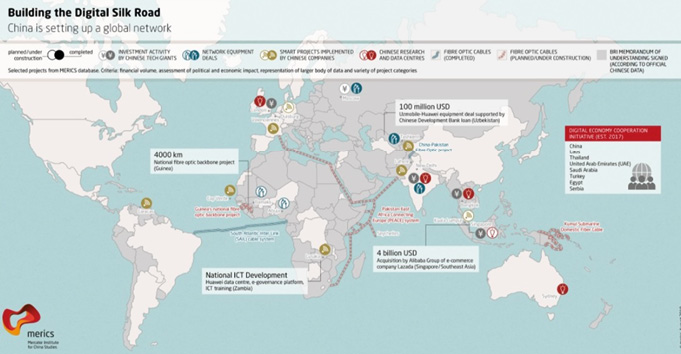

China’s Digital Silk Road (DSR) has financed projects in over 40 countries, with official funding surpassing $17 billion since 2015 (Wiater, 2025; ITU, 2023). These projects often include export of Chinese technical standards, software, and surveillance technologies, embedding Chinese influence in partner nations’ digital ecosystems.

Conversely, the US counters with strategic initiatives like the Clean Network and Blue Dot Network, and with regulatory measures including export controls and investment screening. Yet, the US faces persistent workforce shortages and underinvestment, as noted by DUCATUS Partners 2 (2018), calling into question its capacity to sustain digital leadership.

Case studies such as Kenya’s Huawei-powered networks, Brazil’s CBERS satellite collaboration, and Argentina’s Neuquén deep space station exemplify the geopolitical consequences of digital infrastructure choices and illustrate the strategic vulnerabilities and dependencies that can emerge for third countries (Prasad, 2025).

Structure

Section 1 reviews the theoretical frameworks and methodology. Section 2 analyzes the global infrastructure competition with empirical case studies and figures. Section 3 examines innovation and corporate strategy, integrating DUCATUS findings. Section 4 explores cybersecurity, drawing on scholarship and organizational reports. Section 5 projects future scenarios and policy recommendations. Section 6 analyzes Latin America as a critical arena. The conclusion compares objectives and results, with a special focus on Latin America.

Theoretical Framework and Methodology

Theoretical Framework

This study draws on three primary strands of international relations theory:

- Techno-nationalism: States pursue technological supremacy as a means of securing sovereignty and strategic autonomy, often through aggressive industrial policy, export restrictions, and technological protectionism (Jin, 2025; Chatham House, 2024). US and Chinese techno-nationalism manifest not only in trade wars but also in global standard-setting bodies and supply chain strategies.

- Complex Interdependence: Digital connectivity creates deep economic ties and new vulnerabilities, increasing both the incentives for cooperation and the risks of conflict (Pisani, 2025; Keohane & Nye, 2012). This interdependence manifests in globalized supply chains, cross-border data flows, and shared technological platforms, but also in mutual exposure to cyber threats and systemic shocks.

- Regime Theory and Digital Sovereignty: Competing global governance efforts to set standards for data, infrastructure, and cybersecurity (ITU, 2023; von Solms & van Niekerk, 2013). The struggle to define “digital sovereignty” pits US advocacy of open, market-driven networks against China’s state-centric, security-driven approach.

Through these lenses, the US-China rivalry is understood as a hybrid contest—simultaneously zero-sum (strategic) and positive-sum (innovation-driven), with major implications for third countries and the global commons. The study also introduces the concept of “technological bifurcation,” where global digital infrastructure and standards split along geostrategic lines, producing systemic inefficiencies and governance gaps.

Methodology

This is a qualitative, comparative policy analysis integrating:

- Case studies: Focused on DSR funding in Kenya, Brazil, and Argentina; comparison to US initiatives in the same regions.

- Document analysis: Official reports from international organizations (World Bank, DUCATUS PARTNERS, ITU, OECD, RAND), US and Chinese government documents, and regulatory filings.

- Academic and organizational review: Perlroth (2021), Thomas (2025), Barna et al. (2025), Chatham House (2024), Pew Research, and others.

- Figures and tables: Investment flows, cyber operations, project maps, and timelines (see Figures 1–3).

- Integration of DUCATUS findings: On workforce, innovation, and governance, with particular attention to policy recommendations and future scenarios.

The Global Infrastructure Race: Digital Silk Road vs. Clean Network

The competition between the United States and China for digital infrastructure dominance is central to their technological rivalry, with profound international political and economic implications.

Digital Infrastructure Development

Both nations aggressively pursue leadership in artificial intelligence, computing systems, 5G/6G networks, data centers, cloud computing, and quantum research (Arciniegas, Quimbre, et al., 2024; Jin, 2025). These domains are not only commercial battlegrounds but also critical to national security and societal resilience.

RAND research documents China’s lead in ultra-high voltage (UHV) power transmission and submarine cable technologies (Arciniegas et al., 2024). China has implemented 34 UHV lines domestically; the US has none. The US faces workforce shortages and project delays; China’s state-driven model enables rapid infrastructure completion (DUCATUS, 2018). Moreover, China’s technological investments are often bundled with financial incentives and political conditionality, making them especially attractive to developing nations seeking rapid modernization.

The Digital Silk Road Initiative

China’s Digital Silk Road (DSR), part of the Belt and Road Initiative, finances digital infrastructure worldwide, particularly in developing countries (Wiater, 2025; ITU, 2023). Huawei’s networks in Kenya, Brazil’s China-Brazil Earth Resources Satellite (CBERS), and Argentina’s Neuquén ground station exemplify China exporting its digital technology and influence (Prasad, 2025). The DSR also extends to e-commerce, smart cities, and surveillance systems, raising concerns over digital authoritarianism, privacy, and dependency.

Figure 1. Map of Digital Silk Road Projects by Region

Source: Wedell (2020).

U.S. Strategic Response

The US responds with export controls, strategic alliances (Clean Network, Blue Dot Network), and domestic innovation investments (OECD, 2023; Bao, 2025). DUCATUS (2018) highlights US workforce shortages that threaten infrastructure competitiveness. The Clean Network framework seeks to exclude Chinese vendors from critical infrastructure but often lacks the financial firepower and diplomatic engagement of Chinese initiatives. The US also promotes an “open internet” vision but faces challenges in convincing partners skeptical of its surveillance practices and regulatory consistency.

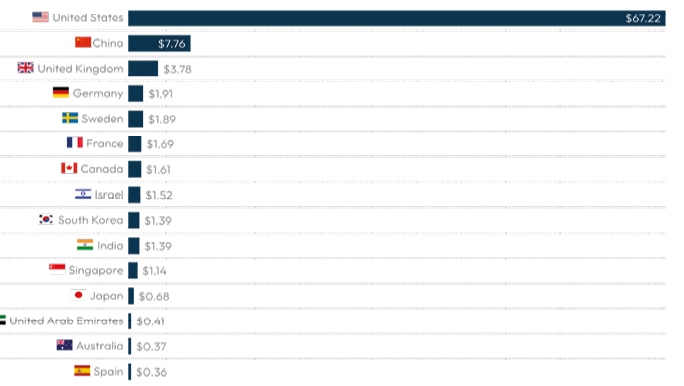

Figure 2. Private Investement in AI by Geographic Area, 2023. In billions USD

Source: World Bank (2024), SEMI (2025), DUCATUS (2018)

Regulatory Environment

Table 1. Key US and Chinese digital regulatory milestones (2017-2025)

| Year | United States Policy/Initiative | China Policy Initiative |

|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Launch of the Clean Network | Implementation of Cybersecurity Law (CSL) |

| 2021 | CHIPS Act | Data Security Law (DSL) |

| 2024 | DOJ Finalizes Data Transfer Restrictions | Enforcement of Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) |

| 2025 | Expanded Export Controls and Blacklists | Network Data Security Management Regulation |

These regulatory trajectories reflect divergent philosophies: the US prioritizes market openness and innovation, while China emphasizes data sovereignty and security. The result is a growing incompatibility in technical standards, data flows, and cross-border investment regimes (PIPER, 2025; Polk, 2025; OECD, 2023).

Data Governance and Digital Sovereignty: Competing Models

The bifurcation of global digital governance is one of the most consequential outcomes of US–China rivalry.

US Data Policy

The US DOJ finalized a rule (effective April 8, 2025) restricting sensitive data transfers to China-linked companies, aiming to protect national security (Polk, 2025). The US approach is characterized by sectoral regulation, a focus on transatlantic data flows, and an emphasis on the role of private enterprise in digital governance.

China’s Framework

China’s Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), Cybersecurity Law (CSL), and Data Security Law (DSL) form a strict data localization and sovereignty regime (PIPER, 2025). These laws mandate that data generated in China remain within Chinese borders, giving the state sweeping authority over information flows and corporate compliance. This approach is increasingly influential in the Global South, where governments see data localization as a path to digital sovereignty.

Strategic and Economic Implications

The bifurcation disrupts global commerce, complicates compliance for multinationals, and challenges international cyber cooperation (Harrell, 2025; OECD, 2023). It also exposes third countries to “regulatory arbitrage,” where they must navigate conflicting legal requirements, often lacking the capacity to do so effectively. The divergence in data governance models risks undermining the interoperability of digital systems, fragmenting the internet, and reducing the benefits of global connectivity.

Innovation and Corporate Strategy

China is projected to surpass the US in computing revenue in 2025 and lead semiconductor investment with $38 billion projected spend (Lee, 2025; Reuters, 2025). Chinese firms, supported by massive state investment, are rapidly closing the innovation gap, particularly in strategic sectors like quantum computing, artificial intelligence, and next-generation telecommunications.

The DUCATUS project warns of US STEM deficits and supply chain vulnerabilities threatening innovation (DUCATUS, 2018). The persistent shortage of skilled labor in the US, coupled with restrictive immigration policies, impedes the country’s ability to capitalize on its historical innovation edge. Meanwhile, China’s DeepSeek R1 AI model, optimized for software rather than hardware, exemplifies disruptive innovation (Thomas, 2025). Such advances highlight China’s growing capacity not only to absorb but to generate frontier technologies.

These trends are not merely commercial—they have profound implications for military capabilities, economic resilience, and global power projection. The struggle for technological supremacy is thus inseparable from the broader contest for international leadership and systemic influence.

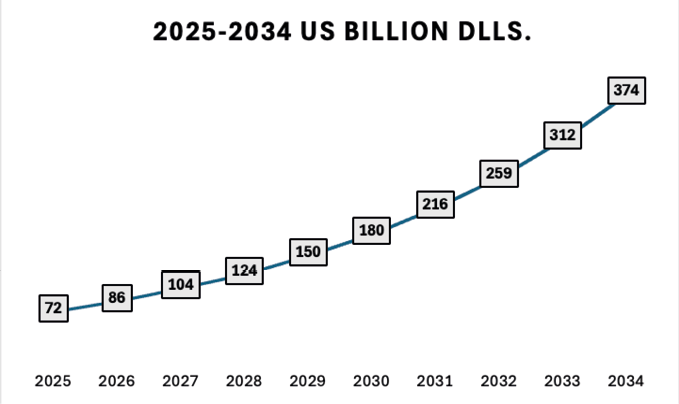

Figure 3. US Next Generation Computing Market Size,2025–2034

Source: (Zoting, 2025).

Cybersecurity: Escalation and Potential Cooperation

China’s state-sponsored cyber operations increased 150 % in 2024–25, targeting critical sectors (CrowdStrike, 2025). Both powers see cyberspace as a domain of strategic competition, with offensive and defensive operations integral to national security doctrine.

Perlroth (2021) highlights vulnerabilities and risks of cyber escalation, including the prospect of “cyber Pearl Harbor” scenarios affecting critical infrastructure. Cultural divides in cybersecurity definitions hinder consensus (von Solms & van Niekerk, 2013; Waterman, 2017), complicating efforts to establish norms and confidence-building measures.

Potential areas of cooperation include AI safety, cybercrime, and infrastructure protection (Schepkov, 2025;). Yet, efforts at confidence-building remain fragile, vulnerable to mistrust and the broader geopolitical context. The escalation of cyber operations increases the risk of unintended consequences and “grey zone” conflict, threatening the stability of the entire international system.

Future Scenarios and Policy Recommendations

Scenarios range from full technological decoupling—where global digital systems split into rival spheres of influence—to managed competition with selective cooperation in areas of mutual interest (Barna et al., 2025; Farrell & Newman, 2019). The risks of decoupling include higher costs, reduced innovation, and the marginalization of less developed economies.

Policy recommendations include:

- US investment in STEM education, research infrastructure, and strategic alliances to maintain competitiveness.

- China’s transparency and engagement in international norms to build trust and mitigate the risks of digital authoritarianism.

- Third countries’ regulatory capacity building to preserve agency, avoid dependency, and maximize the benefits of digital modernization (World Bank, 2024; Chatham House, 2024).

A multilateral approach is essential to prevent the emergence of a fragmented, insecure, and exclusionary digital order.

Latin America: A Crucial Arena

China’s space and digital investments in Latin America challenge US hegemony, exemplified by satellite cooperation, ground stations, and technology transfer (Prasad, 2025). These projects provide critical infrastructure but also embed Chinese standards, giving Beijing long-term strategic leverage.

The US, meanwhile, lacks a coherent regional digital strategy, risking influence loss in a historically strategic sphere (Chatham House, 2024). Latin American countries are not mere passive recipients; they exercise agency in negotiating terms, seeking to maximize benefits while managing dependencies. Nonetheless, the growing asymmetry in resources and technological capabilities constrains their choices.

The region’s experience highlights the broader global stakes: in the absence of coordinated, inclusive governance, digital modernization can deepen dependency and vulnerability, rather than empower autonomy and development.

Conclusion

US-China digital diplomacy is reshaping the global order, generating fragmentation, new dependencies, and systemic risks. The contest between these digital superpowers is not merely a bilateral rivalry but a structural transformation of international politics, economics, and security. Latin America illustrates this dynamic vividly, serving as both testing ground and prize in the evolving technological order.

The future depends on nuanced diplomacy, balancing competition with collaboration to foster resilient, inclusive technological ecosystems, and to prevent the emergence of a divided, unstable digital world (Pisani, 2025; Farrell & Newman, 2019). Only through renewed commitment to multilateralism, innovation, and shared standards can the promise of the digital revolution be realized for all.