Introduction

During the last decades, in the splendor of the free trade model, most of the governments in the world decided to participate in negotiations to reduce trade tariffs and open their economies to producers from different countries. It is assumed that free trade activities and engagement of nations produce important economic results for all the participants, for example, growing gross domestic product, exports, imports, employments, investments and more. The commitment to economic liberalization and market opening promoted large regional groupings and trade agreements worldwide. Because of these policies, different reports from multilateral organizations such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organization and the World Bank mention that global exchange boomed in the decades of 1990 and 2000.

Riding on the wave of these trends, in 2004, Mexico had the opportunity to negotiate an ad hoc economic partnership agreement with Japan. The Asian country represents a strategic alternative to promote economic complementarity because of its global industries, the possibility to attract investments and launching activities related to manufacture and exports, and looking for commercial diversification, so the Mexican government decided to go on and open a new door in the Far East region.

In the case of Japan, the possibility of participation in the Mexican market, became a great opportunity in the perspective of its industrial and political leaders of that moment. Despite the economic capacity of both nations (and unequal for Mexico), the economic association agreement became a new factor of bilateral closeness, however, with the consensus of both sides, therefore it began this new stage in the history of the bilateral relationship.

This association represented a challenge for Mexico for taking advantage of the opportunities offered in the Japanese economy and to strengthen its commercial position. For Japan, this meant a way to find new suppliers and raw resources from Mexico to complete productive activities. Since promoting the initiative through a free trade agreement, this association represented a great negotiation effort, despite the asymmetry of both economies.

Considering the topics of the negotiation, the representatives of both nations decided to include rules related to market liberalization, customs procedures, certification of origin of merchandises, bilateral cooperation and other guidelines. The idea was to make atractive the terms of market, to impulse bilateral economic activities, therefore create great expectations for Tokyo and Mexico this new Trans-Pacific association.

Thus, it will be important to analyze over time the performance of Mexican companies in the Japanese market considering that they could acquire experience and comparative advantages through know how, manufacturing experience, investment, and collaboration. On the other hand, it will also be important to observe the performance of Japanese companies in its trade activities in Mexico to complement the manufacturing and production of goods for the domestic market and new exports for the international economy.

In this paper it is examined the performance of trade and investments activities of Mexico and Japan in the operating scenario of the Economic Partnership Agreement in two different moments; the first one, when the agreement came into force, just in the time of boosting economic dynamics in 2005; and at the second one, at the end of 2023, in order to explain how useful, efficient and appropriate has been the use of the agreement for companies and producers of both sides.

To achieve this goal, the methodology developed in this paper is the simple comparison of quantitative data of the activities that both nations have had in in the period from 2005 to 2023. It will be considered the financial result of trade and investments, the exchange relation between both countries and the type of goods that are most commercialized. It will also be important that the data analysis will correspond to the economic environment driven by globalization implemented through liberal policies among the states and the dynamics of the Mexico-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement. Therefore, both countries have the opportunity to demonstrate that almost 20 years after this agreement came into force, that all economic and cooperation activities could reach good results through complementation and concentrate the market efforts in sectors associated with competitiveness.

Economic liberalization, trade and globalization

In recent decades the opening of markets through economic liberalization has been in the debate, discussions, and political decision-making process, when governments adopt a strategy trying to get benefits or protect their productive sectors. During the years of 1990, numerous governments worldwide assumed that less intervention in the economy and opening the market to producers of goods and services will favor the development, growth, and expansion of productive activities3.

Trade policies lead governments to conduct negotiations to achieve free trade goals and are congruent with the fact related to getting results in economic growth and gaining access of their producers to participate in international markets. According to the theory of international commerce that makes competitive companies and producers in a globalization environment. And as a consequence, from 1995 to 2012 thirty countries not only adopted liberal economic policies, but became members of the World Trade Organization and contributed to impulse –in the midst of competition of great Powers– a favorable environment for the liberalization and facilitation of trade4.

It is important to mention that in negotiations it is necessary to consider the trade of services for the flows of investments, and capital resources 5. When the opening to trade in services is included in the strategy, the flow of resources creates favorable conditions to even stimulate economic growth from globalized industries and the development of international projects.

This is the basis of the economic liberalization strategy. These circumstances contribute to create absolute and comparative advantages, therefore specialization in production and it is possible to achieve economic efficiency through international trade6. If a nation is more efficient producing some goods in conditions of comparative or absolute advantage it will be convenient to exchange goods with a different country (Krist, 2014).

Another factor that will also contribute to the liberalization environment is the reduction of taxes on foreign trade to facilitate the flows of goods. Therefore, stimulation of exchange through low tariffs in customs make an important mix of circumstances because it could lead to growing economic results in trade and gross domestic product, particularly when companies are engaged in international markets and production grows because of the supply and demand of goods and services in other countries. Thus, in international experience, since the implementation of negotiations to reduce trade tariffs, world trade has grown particularly due to economic liberalization as it shown in the table 1.

It is assumed that if liberalization environment contributes to specialization, acquisition of comparative and absolute advantages among producers of different countries, it promotes expectations of economic growth,7 increase trade and generate benefits for the countries involved8. As an example of the results of these policies adopted by different countries, in table 1 can be seen and compared some nations that are characterized by open economy strategy and its impact in growht of gross domestic product in selected years (Japan and Mexico are included).

Table 1. Growth of Gross Domestic Product in selected countries (countries characterized by liberalization and free trade strategy)

| Country | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2004 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 1.9 | 2.7 | 4.1 | 3.9 |

| European zone | 2.5 | 2.4 | 3.8 | 2.2 |

| Japan | 5.6 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.4 |

| Mexico | 5.2 | -6.3 | 4.9 | 3.9 |

Source: Information collected from Datos Macro. PIB de los EUA. https://datosmacro.expansion.com/pib/usa?anio=1990.

Datos Macro. PIB de la zona Euro. https://datosmacro.expansion.com/pib/zona-euro.

Datos Macro PIB de Japón. https://datosmacro.expansion.com/pib/japon?anio=2005 and

INEGI. Sistema de Cuentas Nacionales de México https://cuentame.inegi.org.mx/economia/pib/grafica-PIB.pdf

It can be seen then that the contribution to economic growth through international commerce impacts the dynamics of gross domestic product. As evidence of this correlation, it is convenient to adopt and maintain when necessary, a liberal strategy to get the desired result of free trade strategy. As shown in table 1, not only the U.S. and Europe, but Mexico and Japan have gotten growing results except for 1995 when different crises irrumped in the landscape of both nations. As it is known, Mexico has opted for a free trade strategy based on economic openness and, therefore, has obtained growing economic results. Since the entry into force of the then North American Free Trade Agreement (now the Mexico-United States-Canada Treaty), free trade has made the country one of the most important exporters worldwide (Villarreal, 2017).

In the case of Japan, its participation in regional forums such as the Asia Pacific Economic Council (APEC), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN plus three –Japan, China and South Korea), the WTO, etc., has led to the consideration of the economic opening strategy with key countries. The Japanese global companies have also contributed to expand in international markets, so the panorama also looks congruent with liberal policies. The opportunities created by the Japanese government have setting Mexico as a country to supply and participate with in a commercial partnering to achieve market expectations.

As it is accepted that liberalization of markets makes gaining producers engaged in activities in different countries, in the first years of the decade of 2000, in a moment of negociation of free trade agreements and looking for possibilities of exchange, the governments of Mexico and Japan met in 2004, and associated to create an ad hoc environment in the benefit of their companies and consumers. Both governments agreed to establish an Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) based on the liberalization of trade between both parties. The goals of the agreement were set to increase trade, strengthen opportunities for producers in both countries, promoting the companies and producers to guarantee and achieve the complement of economies.

Thus, the specialization that Mexican industries have before achieved with their participation in international markets can boost their presence in the Japanese economy9. In the same way, Japanese companies and producers will find excellent opportunities and market possibilities by participating in the Mexican economy10. Finally, it should also be considered that the Agreement represents a strategy in geoeconomics11 because Mexico diversifies its markets in East Asia and Japan gains greater presence in the North American region. The agreement represents opportunities, despite the unequal conditions of participation and it will be important to understand how complementarity play a role with the producers involved in both markets.

Brief economic outlook between Japan and Mexico before EPA (1990-2004)

The world became more interdependent and connected in the decade of 1990, and NAFTA, APEC, WTO, and different regions, free trade agreements and institutions highlighted in the dynamics of integration or opening of markets, therefore, Japan and Mexico faced a stronger influence of globalization than ever before. It is important to provide a brief overview of the respective histories of Japan and Mexico and their relationship since the late 20th century. Moreover, it focuses on the period of 15 years, from 1990 to 2004, prior to the signing of the Japan-Mexico Economic Partnership Agreement, using data from different international reports.

At the beginning of the decade of 1990, Japan had a rapid growth with an annual average of 5-6 % and especially a kind of “Bubble economy” (Macrotrends, 2024). However, it marked a complete turnaround from the astonishing economy in the nineties. The Bubble burst in 1991 and the country entered in a long period of a great recession, which was called later the “Lost Decade” (it was further extended to “three decades”)12. This is one of the reasons about how to creat solutions to economic problems because the abundance of bad debt remained in Japan and to think how to resolve the crisis. Moreover, the Asian currency crisis, which occurred in Thailand in 1997, worsened the Japanese economy. No major negative economic events occurred other than the above, but that did not mean that the economy recovered.

As for economic partnerships with other countries, Japan became one of the original members of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation Forum (APEC) in 1989. At that time, however, the Japanese government had less interest in Free Trade Agreements (FTA) with specific countries. This attitude changed because FTAs were becoming more widespread worldwide and because of the need to recover from the Asian crisis. Singapore became the first country with which Japan signed the economic partnership agreement (effective 2002). It was also the only country as of 2004, before the birth of EPA between Japan and Mexico.

In the case of Mexico, the country implemented a major economic transformation during the decades of 1980 and 1990, passing from traditional Import-Substitution Industrialization (ISI), which had been promoted since the decade of 1940 to a free market economy. This structural change stabilized the Mexican economy again, albeit with several years of stagnation.

In the wave of liberalization, Mexico signed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with the U.S. and Canada in 1992 (and entered into force in 1994). NAFTA led to increased exports, an influx of foreign direct investment, and high economic growth. Amid the booming economy, in late 1994 the Mexican government announced a 15% devaluation of the peso against the USD. Less than a week later, the value of the peso was halved. This currency crisis affected not only neighboring Latin American countries but also Asian countries and parts of Europe (the Tequila Shock). A relief program was implemented by the United States, the IMF, and the G-10 countries ended the crisis the following year (Villarreal, 2017).

As for economic partnerships, the Mexican government took a positive stance on Free Trade Agreements. In addition to NAFTA, Mexico signed with Uruguay (2003), Israel (2000), Chile (1998), European countries (1997, 2000), and Colombia (1994) as of 200413.

The economic relations between Japan and Mexico

The economic interaction between both countries has been characterized by a small commercial exchange due, in the case of Mexico, to the strong relationship with the United States and the subsequent North America Free Trade Agreement. As far as Japan is concerned, it is a similar situation with its trading partners in East Asia as the main markets for its products.

Taking stock in the economic relations between Japan and Mexico, it is important to mention that in 1990, the value of exports from the Eastern country to Mexico was around 1% of Japan’s total exports ($1,283 US million dollars) and showed no significant changes over the period 1990-2004 (WITS, 2024). As for imports, they accounted for 0.8% in 1990 (1, 440 US million dollars) dropped to 0.5% through 1992 and continued through 200414.

In the case of Mexico, on the other hand, as of 1990, exports from Mexico to Japan accounted for nearly 5% of Mexico’s total exports but dropped below 2% through 1997 and continued through 2004. Imports accounted for nearly 6% of total imports in 1990 but dropped to 2% by 2002 (WITS, 2024). However, in 2003 and 2004, there was an upward trend. The economic interdependence between the two countries is very small; in fact, it has weakened further in the 15 years between 1990 and 2004.

On the other hand, regarding flows of capital, foreign direct investment also tells us a similar story in the economic relationship between both countries. The amount of Japanese direct investment in Mexico during 1990 was 1,874 U.S. million dollars (Szekely, 1994) and 463.85 million USD, as average during 1990-1994 which accounts for just 0.2 % of the total amount. There is no data about Mexican foreign direct investment in Japan, but it is estimated to be zero or near zero.

Lastly, we mention cooperation, not interdependence. Japan, the second-strongest economy in the world as of 2004, with a GDP seven times that of Mexico, often provided assistance to Mexico. When the Tequila crisis occurred in 1994, Japan offered emergency financial assistance to Mexico. Moreover, as part of its Official Development Assistance (ODA), Japan, through the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA)15, provided technical cooperation, paid financial cooperation, and grant assistance to Mexico. Many projects were implemented in diverse sectors. The supporting sectors ranged from health care, environmental conservation, agricultural development, water resources, disaster prevention, and private sector development.

From the above, and because the size of the economies and the characteristics of both countries, as shown in table 2, it can be said that prior to the conclusion of the Economic Partnership Agreement, there was a stronger one-way cooperative relationship in which Japan supported Mexico rather than a relationship of interdependence or like economic partner.

Table 2. Basic data of Japan and Mexico as of 2004

| Japan | Mexico | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | 127,761,000 | 103,945,813 |

| GDP (billion USD) | 4,902.29 | 747.66 |

| Income per capita (USD)* | 29,634 | 6,063 |

*Adjusted net national income per capita (current US$)

Source: Created by the author based on World Development Indicators from World Bank. It is important to note the asymmetry in the economy of both nations and some fundamental indicators.

The previous table also shows that in 2004 the productive capacities and the income level is too disproportionate. Although by then Mexico already had different trade agreements in place, the experience of economic growth is very different from that of Japan.

The impact of trade in the growth of gross domestic product is related in the way the economy of both countries adopted open market strategies and faced the waves of globalization (crisis and stability in international economy).

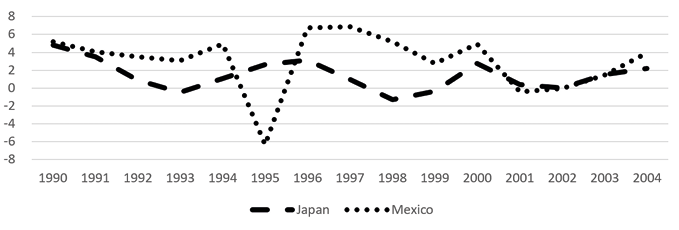

As shown in figure 1, in the years of 1995 and 2001-2004 were critical moments in the history of economic relationship because of the difficulties generated by the devaluation in Mexico and then the events of 11S in the U.S., so its impact in the trade, production led to a fall in this indicator and then the effects of the recovery strategy adopted by the Mexican government could solve the situation. In the case of Japan, a similar critical situation is shown and associated to the moments of the prolongation of negative effects over time and its impact in the growth of gross domestic product.

The evolution of the GDP growth rate in figure 1 shows the business cycle faced by the Japanese economy. It marked 5% of the GDP growth rate in 1990, dropped to negative after the burst of the bubble economy, and then, after a recovery trend, plummeted again to nearly -2% in 1997 when the Asian currency crisis broke out. It remained stagnant between 0 and 2% thereafter.

Figure 1. Real GDP growth (%) in Japan and Mexico, 1990-2004.

Source: Created by the author based on World Development Indicators from World Bank.

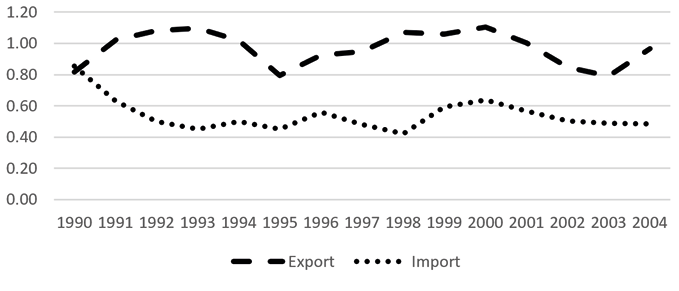

And now, considering 100% of trade relationship it is shown in figure 2 that the years before the Economic Partnership Agreement the participation of Japanese producers in the Mexican market was very small. Considering the nature and structure of trade between both parts, Mexico exported raw materials, petroleum and vegetables, fish, fruits, cotton, coffee, meats and salt (Solís, 2000). On the other side, Japan exported manufactured products. This explains an exchange relationship in which countries have products that complement economic needs from a perspective of raw materials and manufactures in exchange for manufactures with sophisticated processing.

Although trade relations between Japan and Mexico are small in the context of their total exchange, figure 2 explains the trend that shows Japan gains´s in terms of trade. It is necessary to recognize that as Mexico’s trade relations advance, the general trend in trade with Japan has not crucial change before the Economic Partnership Agreement enters into force.

Figure 2. Japanese trade (%) with Mexico as a share of total (before Economic Partnership Agreement).

Source: Created by the author based on World Development Indicators from World Bank, and the Ministry of Finance – Japan.

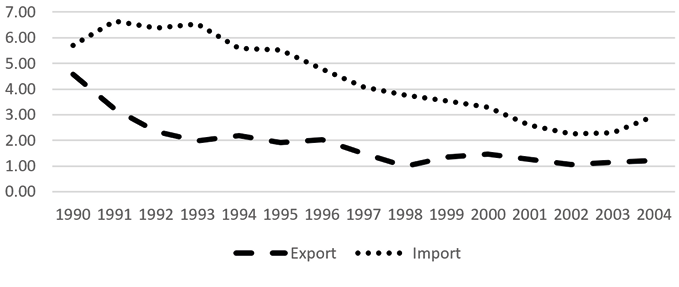

It can also be seen that Mexico's commercial dynamics have been experiencing a decline in its exports with Japan, taking into account that in 1994, when NAFTA came into force, it has greater preponderance in its economic relations. And as free trade strategy of Mexico has been mainly associated to the United States and Canadian region, the participation of Mexican producers with Japan has decreased during the years before 2004 as is it shown in figure 3.

The causes of these circumstances are multifactorial. There are different perspectives that can, in addition to NAFTA, explain this trend. Since the geography, culture, language, and more, different factors make crucial trade relationships. As both countries are so far each other, it is necessary to understand that the functionality of an agreement with Japan and the possibilities of complementarity will depend directly on those productive sectors that are compatible with the industries of the eastern country and the economic needs of both parties.

Figure 3. Mexican trade (%) with Japan as a share of total

Source: Created by the author based on World Development Indicators from World Bank, and the Ministry of Finance – Japan.

The Economic Partnership Agreement and dynamics during 2005-2023

After assessing all international economic trends and considering the need to set a formal agreement, the governments of Mexico and Japan decided to negotiate an Economic Partnership Agreement. It was not an easy way to walk because of the asimetry of economies and political visions. Before the negotiations, it was really difficult to convince the member of the political class in both countries (Traslosheros, 2021). It is considered that there was an oppsoition in Japan, after analyzing and tought if Mexico was ready for a treaty and concluded that it was necessary to improve production conditions in different sectors. In the case of Mexico it was necessary to convince Japanese negotiators about opening conditions in the Japanese market for Mexican producers16.

After different efforts (14 rounds), both governments decided to negociate and organize the official teams to represent national interests and gather. Finally, in 2004 when Vicente Fox was the President of Mexico and Junichiro Koizumi the Prime Minister in Japan both nations agreed to carry out the treaty. From Mexico’s perspective, this agreement represents access under preferential conditions for its products to the third largest market in the world after the United States and the European Union. It also is important because is a way to expand the country’s commercial presence in the Asia-Pacific region and strengthen economic ties through high-level government and business sector groups17.

The complex productive network that includes different industrial sectors fosters the interrelation of companies that require supply and manufacturing of high-quality standards for international markets. These circumstances made the Japanese industries and market atractive for Mexican producers to find new business opportunities. In addition to those ones, in 2004 Japan was ranked as the second country with the greatest export potential in the world and Mexico also had the possibilty to became an important trade partner in Latinamerica (Traslosheros, 2021). It is also important to mention that due to the interaction of Japanese companies worldwide, for Mexico was a very good moment to engage and strengthen supply and economic complementation in different productive sectors.

Considering all possible expectations to promote bilateral exchange, the governments of Mexico and Japan established the Economic Partnership Agreement with the purpose of liberalizing trade between both parties, promoting cooperation and promoting trade in goods, services and capital (SICE, 2004).

Based on these guidelines, the negotiators concluded the treaty 18. Some topics of the content of the agreement includes:

- Access to markets.

- Rules of origin.

- Certificate of origin and customs procedures.

- Sanitary and phytosanitary standards.

- Standards, technical regulations.

- Safeguards.

- Investment

- Services

- Government purchases

- Competition, and

- Dispute resolution.

The agreement has a simmilar structure of free trade treaties and an institutional framework that made possible the immediate accesion to Mexican producers to the Japanese market in the case of 95% of negotiated merchandises, and for the Eastern nation it was the case for 44% of their products.19

As a consequence of the entry of force of the agreement, trade and investments increased 37% in its first year. It is also important that due to the characteristics and size of the Japanese economy, industries and its comparative-absolute advantages, the exhange relationship became greater and made a good perfomance that is shown through the time.

Since the first years of operation of the agreement, both nations have faced different situations, as well as the effects of critical moments that have required greater rapprochement and cooperation. These years have had sweet and bitter moments in the world economy and trade. From those first days of optimism and great expectations to the occurrence of events that have led to trade protectionism.

And now, 18 years have passed since that distant April 1, 2005, when the Mexico-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement came into force. At that time, our countries made a commitment to strengthen market opportunities for business communities on both sides of the Pacific.

The agreement has led to contrasting results, since the different provisions on market access, rules of origin, as well as issues on companies and the business environment have been a joint work framework with important challenges for Mexico and with a very asymmetric balance in favor of Japan, as it can be seen in table 3:

Table 3. Trade balance between Mexico and Japan 2005-2022

+(Selected years and U.S. million dollars)

| Year | Mexico | Japan | Total of bilateral exchange | Balance (In favor of Japan) |

Percentage of total exports Mexico to Japan |

Percentage of total exports Japan to Mexico |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | $ 1,470 | $ 13,077 | $ 14,547 | $ 11,608 | 0.69% | 5.9% |

| 2010 | $ 1,925 | $ 15,014 | $ 16,939 | $ 13,089 | 0.65% | 4.98% |

| 2015 | $ 3,017 | $ 17,369 | $ 20,386 | $ 14,352 | 0.79% | 4.39% |

| 2020 | $ 3,652 | $ 13,896 | $ 17,548 | $ 10,244 | 0.88% | 3.63% |

| 2022 | $ 4,703 | $ 18,297 | $ 16,778 | $ 13,595 | 0.81% | 3.03% |

Source: Created by the authors based on Secretaría de Economía. Estadísticas del Comercio Exterior. https://www.economia.gob.mx/files/gobmx/comercioexterior/estadisticas/Anual-Exporta-2021.pdf (for exports from Mexico to Japan)

As an example, bilateral trade has grown in proportion to the comparative and competitive advantages of producers. In 2005, exports from Mexico to Japan totaled $1.47 billion dollars. For 2021 these reached $4,182 million dollars. In the case of imports, in 2005 purchases were registered from the eastern nation for $13,077 million dollars, while in 2021 these reached $17,084 million dollars (Data Mexico, 2024). In short, the general balance is a favor for the Asian country, which is several times greater than Mexico’s commercial capacity.

While trading amount has increased, the share has not changed. A share of Mexican trade with Japan as of 2022 is 0.3% for exports and 3.0% for imports. It is almost the same as the share before EPA. On the other hand, a share of Japanese trade with Mexico as of 2022 is 1.6% for exports and 0.7% for imports. Both are slightly higher compared to 2004. The amount of trade between the two countries increased after EPA but its presence each other has not changed due to the increase of the total world trade. In this scenario of unequal exchange, among the trading products there are goods as minerals, vehicles, auto parts, electrical devices, laminated steel and food products (Data Mexico, 2024).

In a similar perspective, investments have experienced equally valuable dynamism. In 2005, Japanese investment in Mexico was $335 million dollars. In 2022, this reached $2,171 million dollars, essentially concentrating in Guanajuato, Aguascalientes and Mexico City. As far as our country is concerned, opportunities are located in the entertainment, food, manufacturing and auto parts sectors, to mention some potential areas20.

These 18 years have been one of complete transformation of the world economy and our countries seek to achieve new horizons. Today, faced with the different geopolitical challenges and commercial and technological competition between powers such as the USA and China, it is important to find alternatives to improve the conditions of international geostrategic participation.

Therefore, this institutional framework will remain as an ad hoc work scheme to explore and exploit the great market potential for Mexican business. Without a doubt, this will continue to contribute to the transformation of our economies and regions. And although on the path taken there are other participation mechanisms such as the Asia Pacific forum (APEC) and the Trans-Pacific Partnership, our countries must continue with dialogue, mutual learning and the creation of opportunities to maintain an environment of excellent relations21.

Depending on the pace of expectations, the establishment of new investments, the promotion of business integration, alternatives will continue to emerge throughout the geography of Mexico and Japan. To this will also be added cooperation, educational and cultural exchange to strengthen bilateral ties. In short, our countries must take advantage of the circumstances of global economic transformation, convert risks and threats into successes and make this potential one of the competitive characteristics of the association that distinguishes both countries.

Conclusions

After generally reviewing the different stages through which the Mexico-Japan Economic Association Agreement has gone through, it is advisable to make some conclusive reflections. This is an agreement proposed, planned and launched in 2005. The commercial and global economic environment was very different from our time. However, the initiative has met great expectations for both parties in its purpose of increasing bilateral trade and economic activities.

This agreement, typical of the Transpacific scenario, has represented a strategic association for the governments of both countries. Therefore, it can be mentioned that there are gains, but also not so favorable results in some aspects. The agreement has also represented an opportunity for economic complementarity that can be seen in the different sectors that have benefited from the opening of the market.

For Mexico, this agreement represents an opportunity to diversify its international economic relations and also an alternative to maintain interaction in the region with greater dynamism in the contemporary world economy. In addition to achieving growth in exports to the eastern country, this agreement has represented an opportunity to promote economic complementarity and favor productive sectors whose comparative and absolute advantages have allowed them to participate in that market.

For Japan, the agreement has meant a greater presence in the Mexican market and economy. At the same time, we took advantage of opportunities to further promote investments in strategic sectors, primarily the automotive sector. The Eastern country has gained a lot through investments and exports to Mexico, therefore also contributing to boosting the foreign trade of the American country.

Although there is a very favorable exchange relationship for Japan, the gains for both parties can be seen in the economic complementarity in the different productive sectors that participate in this market dynamic. Mexico is winning, although not much in this agreement, but it has benefited from the increase in exports to Japan and also from the placement of strategic investments in its national territory. At the same time, it has allowed the productive consolidation in the automotive sector and a very favorable environment for potential economic activities to which the initiatives of new producers can be added in the present and future. In the case of Japan, the growing presence in a market close to the United States should also be highlighted to favor the expectations of producers who indirectly participate in the North American region. Additionally, at the geostrategic level, given China’s strong commercial presence, the agreement leads to strengthening ties with countries outside its geoeconomic zone and attracting valuable resources for the national economy.

The agreement, the results achieved, the business communities and benefiting producers of both parties still have a lot to do. The current economic and commercial scenario in the world is one of great competition and rivalry between great powers. Mexico and Japan still have a lot to do, to achieve better results despite the fact that the current panorama is too asymmetrical and in favor of the Eastern nation. Although this agreement has also given good results to Mexico, but with a very unequal circumstance, it faces the challenge of strengthening its productive capacities and market intelligence to find new opportunities.

At the current time, and although the agreement has already undergone an update, it stands as a challenge in which governments, business communities, entrepreneurs and other project leaders must learn about and mutually promote new initiatives to give greater strength to this bilateral strategic partnership. So it is important to consider that as the results are very similar to the 2004 conditions, the agreement must continue recognizing the challenges that both countries need to face.