Introduction

As the world’s most populous country, China has always been a global economic powerhouse. However, with demographic change sweeping across the nation, its traditional growth model is set to undergo significant transformation in the coming years (Li, 2015). From the one-child policy to an aging population and shrinking workforce, these trends are reshaping China’s economy in ways that will impact not only its citizens, but also nations around the world. This essay explores how demographic change is influencing China’s economic future and what it means for businesses operating within its borders. The undergoing demographic transition in China, implies pressure on labor supply for the industry over the coming decades. Based on data, mainland China’s population fell 850,000 to 1.41bn in 2022 – the first decline in six decades-. The current birth rate for China in 2023 is 10,645 births per 1,000 people, a 2.36% decline from 2022 (Statista, 2017) (See graphic 1 and table 1).

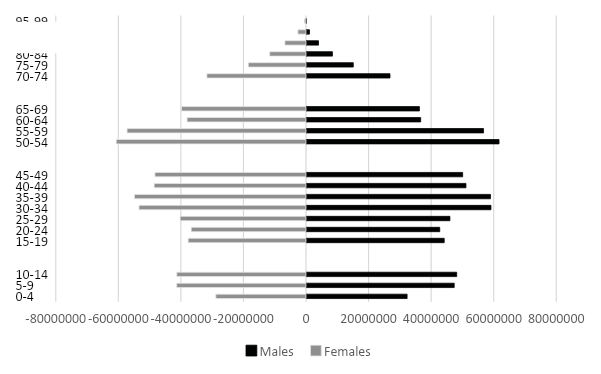

Chart 1. China’s 2023 Population’s Trends

Source: PopulationPyramid.net (Population Pyramids of the World from 1950 to 2100, 2010).

It is relevant to the analysis of Chinese demographics to note that prior to the one-child policy established in 1979, the population pyramid was in the direction of a gender balance with a slight tendency towards a female surplus, but with the implementation of population controls from 1980 to 2015, the population balance between genders was distorted. According to Chinese population data, in 2023, there are more Chinese females in the range from 55 to 99 years old. Furthermore, men over the age of 55 were more likely to be victims of the Maoist revolution, the cultural revolution, forced labor, and infectious diseases like pneumonia or coronavirus. Michael Schuman of The Atlantic magazine suggests, according to independent experts “skeptical of Beijing’s official data”, that, approximately, COVID-19 deaths were ranging from 1 million to 1.5 million deaths, maybe more men than women (Schuman, 2023).

Table 1. 2023 data

| Age | Males | Females |

|---|---|---|

| 0-4 | 32318569 | 28826052 |

| 5-9 | 47383460 | 41333615 |

| 10-14 | 48174207 | 41305036 |

| 15-19 | 44,185,169 | 37,675,535 |

| 20-24 | 42,752,184 | 36,683,449 |

| 25-29 | 46002635 | 40232687 |

| 30-34 | 59129589 | 53395144 |

| 35-39 | 58979445 | 54848838 |

| 40-44 | 51128552 | 48550099 |

| 45-49 | 50073949 | 48295878 |

| 50-54 | 61,710,010 | 60,666,383 |

| Total | 541,837,769 | 491,812,716 |

| 55-59 | 56,752,851 | 57,199,238 |

| 60-64 | 36,656,033 | 38,017,746 |

| 65-69 | 36,253,701 | 39,813,049 |

| 70-74 | 26,850,709 | 31,682,096 |

| 75-79 | 15,120,451 | 18,452,294 |

| 80-84 | 8,451,478 | 11,610,011 |

| 85-89 | 3,999,237 | 6,746,941 |

| 90-94 | 1,112,028 | 2,584,086 |

| 95-99 | 134,381 | 532,052 |

| Total | 185,330,869 | 206,637,513 |

Source: National Bureau of Statistics (NBS, 2023).

Trends and perspectives

China’s demographic landscape is transforming at a rapid pace, and it’s essential to understand the key trends and perspectives driving this change. One of these trends is urbanization, as China’s population shifts from rural areas to cities in search of better employment opportunities and living standards.

If China’s urbanization continues at this unprecedented rate, by 2030 it will score one billion urbanized people, according to McKinsey Global Instituten (2009): “For companies in China and around the world, the scale of China’s urbanization promises substantial new markets and investment opportunities”. This will make a huge advantage for China’s high-tech development and clustering the most skilled workers that could move the country to higher-value-added activities (Statista, 2017).

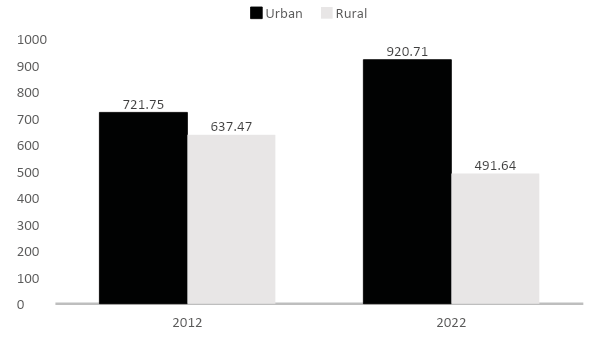

Chart 2. Rural Population Declines

Source: NBS (2023)

Another perspective is technology adoption which has been a major driver of economic growth in recent years. With the rise of e-commerce platforms like Alibaba and Tencent, Chinese consumers have become increasingly reliant on digital services for everything from shopping to banking. But technology adoption and Innovation didn’t drive China’s manufacturing miracle, instead the driver, as some analysts said, might be the “brute-force imitation”. China dedicated itself with great success in getting others’ innovations and in few years catching up the missed Industrial Revolution and being the world’s most modern manufacturing country, overcoming China’s reputation of a “global copycat” as Harvard writer Zak Dychtwald called it (Dychtwald, 2021).

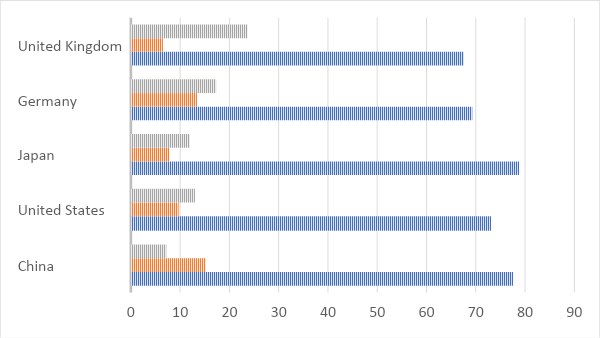

The main drivers of technology innovation in China are private companies and government, less but not least, the universities (see table) (“Is China Leading in Global Innovation?”. 2019).

Chart 3. R&D performed by sector, key countries, 2017

Source: OECD Main Science and Technology Indicators.

However, despite these positive developments, there are also several challenges that must be addressed. For example, income inequality remains a significant issue within China’s society. Additionally, environmental degradation caused by industrialization continues to pose risks both domestically and globally.

In addition to that, the high-speed economic growth since 1980 is the main reason that various pollutants had significantly increased, mainly after China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001 and became the world’s factory. Environmental pollution is such a health burden that according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information caused approximately 1.4 million premature deaths in 2019 (Liu et al., 2020).

While pollution is a major concern, there are certainly other obstacles ahead for China’s economy due to demographic changes such as an aging population and shrinking workforce; its overall trajectory towards becoming a more modernized nation with rising consumer spending power looks promising in the long term.

The One-child Policy and its Impact

China’s one-child policy, implemented in 1979 to control population growth, has had a significant impact on the country’s demographic landscape (Jennifer Hickes Lundquist et al., 2014). The policy restricted most families to having only one child and imposed fines and other penalties for violators.

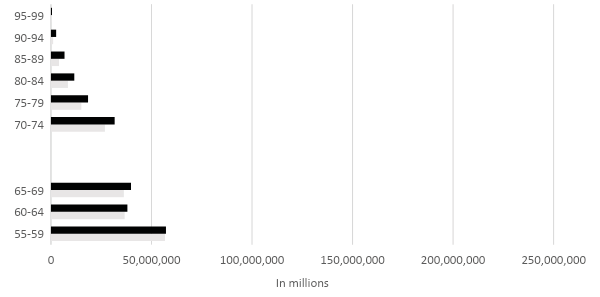

One of the main effects of this policy is that China’s population growth rate slowed down considerably. However, it also resulted in an imbalanced sex ratio as many families preferred male children over females. As a result, there are now millions more men than women in China, except for the different gender imbalances in adults 55 to 99 years old (see Chart 4) (Population Pyramids of the World from 1950 to 2100, 2010). The one-child policy implemented in 1979 distorted the balance between genders whose equilibrium was observed in the population statistics of 2023 where the number of women over 50 years of age is higher than the total number of men, but is disrupted in 1979 onwards, although in 2015 it is considered to have ended. With the increase in income, the greater participation of women in the education and economic sectors, the fertility rate plummets.

Chart 4. China’s population ages 55-99 years old

Source: National Bureau of Statistics (NBS, 2023).

Moreover, with fewer children being born each year due to the one-child policy, China is facing an aging population crisis where there will be fewer working-age people to support its elderly citizens. This could put immense pressure on social security systems and healthcare facilities.

Additionally, some experts argue that the one-child policy led to a decline in fertility rates among educated urban populations who valued their careers over starting families. This could have long-term implications for future generations and may affect economic growth prospects.

While the one-child policy did help regulate China’s population growth initially, it has created various challenges for the country such as gender imbalance and an aging society.

The Aging Population

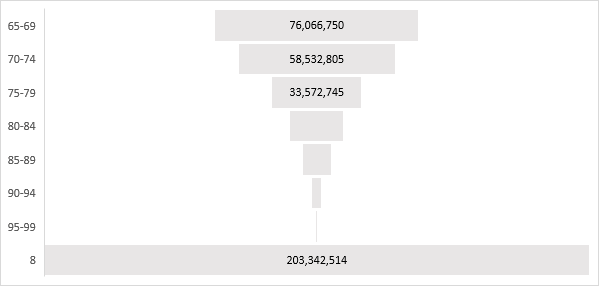

China’s aging population is a major demographic challenge that has been long anticipated. The number of people over the age of 65 has already surpassed 203.3 million (see chart), and this figure is projected to double by 2050. This trend poses significant economic and social challenges for China in the years to come (Population Pyramids of the World from 1950 to 2100, 2010).

Chart 5. Chinese population over 65

Source: NBS (2023).

One of the most pressing issues associated with an aging population is healthcare costs. Older adults typically require more medical attention than younger individuals, which can put a strain on government budgets and resources. In addition, there may be fewer younger workers available to support retirees financially through taxes.

An aging population can also have implications for the labor market. As older workers retire, they may take valuable skills and knowledge with them, creating skill shortages in certain industries or regions. There may also be a shift towards part-time work or flexible schedules as older individuals choose to continue working past retirement age.

An aging population can lead to changes in consumer behavior patterns. Older consumers are likely to have different spending priorities than younger generations and may prefer products or services that cater specifically towards their needs.

China’s aging population presents both challenges and opportunities for policymakers across different sectors of society. It will be important to address these issues proactively in order to ensure continued prosperity and growth for future generations.

The Shrinking Workforce

The shrinking workforce is another significant demographic challenge that China’s economy faces. The country’s working-age population has been declining since 2012 and it is projected to continue doing so in the coming years. In just one decade (2012-2023), China’s workforce lost 20.6 million people (see chart) (Population Pyramids of the World from 1950 to 2100, 2010).

Chart 6. Chinese Workforce 2012-2023

Source: NBS (2023).

This trend results from both a decline in birth rates due to the one-child policy and an increase in life expectancy. As older workers retire, there are fewer young people available to take their place. This situation could lead to labor shortages across various sectors of the economy (Dollar et al., 2020).

What’s more, China’s urbanization drive, over the past few decades, has shifted many rural residents into cities seeking work. However, this flow of cheap labor may not be sustainable as those who have migrated move up the economic ladder.

To offset these trends, policymakers will need to focus on boosting productivity through technological innovation and promoting entrepreneurship at all levels of society. Additionally, they must ensure that workers’ rights are respected while providing adequate social safety nets for those who cannot find employment.

Addressing China’s shrinking workforce requires creative thinking and bold action from policymakers if the country wants to maintain its growth trajectory amid changing demographics (Goodhart & Pradhan, 2020). And, no less important, maintaining better relations with Chinese diaspora and, Taiwanese stakeholders.

The Middle Class

The growth of China’s middle class is one of the most significant demographic changes impacting the country’s economy. The emergence of a consumer-driven society has been fueled by increased urbanization, rising incomes, and changing cultural values.

China’s middle class expanded substantially as its urban population grew from 19 percent of its population in 1980, to reaching 58 percent in 2017. In 2000, just four percent of China’s urban population was middle class, rising to over 30 percent in 2018, in less than two decades (Who Make up China’s Middle Class? We Asked 5 Simple Questions, 2019).

As more Chinese citizens enter the middle class, their spending habits have shifted from basic needs to discretionary items such as travel, luxury goods, and entertainment. This shift in consumption patterns has created new opportunities for businesses, both domestically and abroad.

However, it also poses challenges for policymakers who must balance economic growth with social stability. Rising income inequality between rural and urban areas could lead to social unrest if not addressed adequately.

Furthermore, China’s middle class faces unique challenges such as limited access to quality healthcare and education systems that can hinder their upward mobility. Addressing these issues will be crucial in ensuring continued economic growth while promoting social equity.

The rise of China’s middle class presents both opportunities and challenges for its economy. As this demographic continues to grow in size and influence, policymakers will need to remain vigilant in addressing its needs while balancing competing priorities.

Conclusion

It is evident that the demographic change in China will have a significant impact on its economy. The one-child policy has resulted in an aging population and a shrinking workforce, which could impede economic growth. However, the rise of the middle class presents new opportunities for businesses to cater to their needs.

To mitigate the negative effects of demographic changes, China must focus on implementing policies that encourage fertility rates and address labor market issues. Additionally, investing in education and technology can help improve productivity levels within the workforce.

While there are challenges ahead for China’s economy due to demographic shifts such as Chinese retiring from work or changing demographics overall, it still has vast potential for growth if managed effectively. By adapting to these changes with forward-thinking strategies, China can continue its ascent as one of the world’s leading economies well into the future.

It is worth notice that this essay uses the method of applied demography recognized as a subfield of demography, one that emphasizes practical applications of demographic statistics and methods, especially concerned with present and future developments and spatial variations in population characteristics. As Rowland emphasized:

Applied demography’s future orientation makes population projections a particular interest. Population projections, supplying information about prospective developments, represent a vital application of demography in planning and policymaking. While much needed and relied upon, population projections are sometimes misunderstood and their potential underutilized. This partly reflects the common belief that population projections have but one purpose, to predict the future, whereas projections have varied applications, among which ‘prediction’ is the most tentative (Rowland, 2014).

The vast majority of demographic analyses, especially those concerning forecasts, are aimed at making two basic assumptions: first, economic growth and demographic variations, and second, public policies aimed at presenting a demographic problem. For researchers, it is vital to know these problems in order to open up more research spaces and stimulate, in the case of China, more detailed studies on production, trade, distribution and public spending, all related to its population pyramid (Rowland, 2014).